Long before the world became fixated on renewable energy, recycling, electric cars and what non-sequitur Trump would tweet out next, one environmental issue dominated the headlines above all else.

In the 1970s, scientists discovered that Earth’s primary protection from harmful UV radiation, the stratospheric ozone layer, was thinning at an alarming rate.

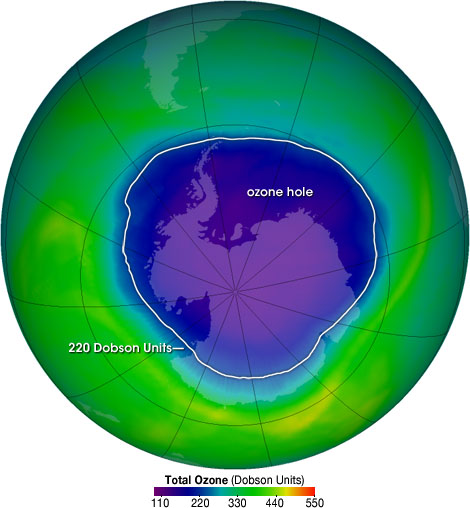

Australia and New Zealand were considered particularly vulnerable due to the biggest ozone hole forming over Antarctica at the beginning of each Southern Hemisphere spring.

The reason for the atmospheric breach, they claimed, was our ever-increasing dependence on products such as aerosols, plastic foams, refrigerants in refrigerators, and air conditioner units in the home and in commercial buildings.

At the time, they all were made with chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), an ozone-depleting gas containing chlorine and bromine, which when broken down could destroy ozone molecules.

Scientists revealed that there was such a proliferation of CFCs – the brainchild of mechanical engineer Thomas Midgley, the American responsible for adding lead to petrol in the 1920s – that urgent action was needed.

In 1987, Australia joined 23 other countries and the European Union to sign the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer (Montreal Protocol). This international treaty, which today boasts some 197 signatories, aimed to protect and restore the ozone layer by phasing out the production and consumption of certain ozone destroying substances (ODS) including CFCs, halons, methyl bromide, and hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs).

Encouraging signs for the future

So, more than 30 years later, just how effective has the ground-breaking treaty been in saving the planet from an environmental disaster?

Our combined efforts to heal the hole, appear to be paying off, according to a new, first-of-its-kind study by NASA that looked at the ozone-destroying chemicals in the atmosphere.

Previous satellite observations had revealed changes in the hole size, noting that it can grow and shrink from year to year. For example, in 2000 and 2006, they were the largest on record, measuring around 32.9 million square kilometres (more than three times the size of Australia) and, for the first time, extending over populated areas.

But the new study is the first to directly measure changes in the amount of chlorine — the main CFC by-product responsible for ozone depletion — in the atmosphere above Antarctica, according to a statement from NASA.

The research, published in January 2018 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, used a Microwave Limb Sounder (MLS) instrument aboard the Aura satellite, and showed a 20-percent decrease in ozone depletion due to chlorine between 2005 and 2016.

“By around mid-October, all the chlorine compounds are conveniently converted into one gas, so by measuring hydrochloric acid, we have a good measurement of the total chlorine,” lead study author Susan Strahan, an atmospheric scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Centre in Greenbelt, Maryland, said in the statement.

“This gives us confidence that the decrease in ozone depletion through mid-September shown by MLS data is due to declining levels of chlorine coming from CFCs.

“But we’re not yet seeing a clear decrease in the size of the ozone hole because that’s controlled mainly by temperature after mid-September, which varies a lot from year to year.”

Parallels to climate change

Although former United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan called the Montreal accord “perhaps the single most successful international environmental agreement to date”, we’ll still need the SPF50 lotion for a good while yet.

Credit: NASA Ozone Watch

“CFCs have lifetimes from 50 to 100 years, so they linger in the atmosphere for a very long time,” said Anne Douglass, a fellow atmospheric scientist at Goddard and the NASA’s study’s co-author.

“As far as the ozone hole being gone, we’re looking at 2060 or 2080. And even then, there might still be a small hole.”

Meanwhile, Susan Solomon, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, co-author of another comprehensive ozone hole study last year, is hopeful the success of CFCs eradication would be a harbinger for international action to avert the worst consequences of climate change.

“Obviously the economics of global warming are different because the fossil fuel industry is worth a lot more in dollars than the companies making these chemicals,” she said.

“But there are important parallels. It was amazing to see how quickly innovation solved the problem with CFCs so we got rid of them yet still have hair spray and air conditioning.

“We’re starting to see the same thing with global warming. We should look at the ozone problem and realise that nations can get together and come up with solutions.”

Image Credit: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uVeTJSIbGm8

No comment yet, add your voice below!